Part 6: Postwar traffic on Wellington

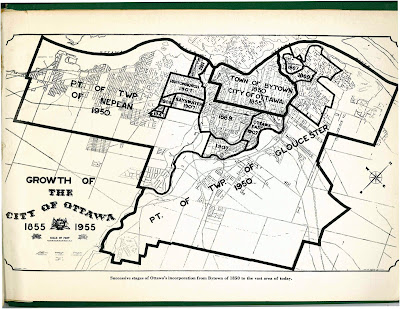

Back in January 2020, we left off with Part 5, in which we watched traffic get heavier on Wellington Street from the 1910s to the 1940s. After a hiatus to do more research and life getting in the way, we're now back to look at government interventions in and around Wellington Street in the ten years following the end of World War II.The biggest change for the City of Ottawa was on January 1, 1950,1 when Ottawa annexed nearly all nearby developed area, including Westboro, Ottawa West, Hampton Park, Highland Park, Woodroffe, Laurentian View, McKellar, Britannia, etc. Thich comprised 7,420 acres (3,000 hectares or 30 square kilometres) of Nepean and Gloucester Townships,2 as seen in the two large sections on the map below.3 Much of this was burgeoning suburban development which fed a daily stream of workers into downtown Ottawa.

Although Richmond Road was thus brought into the City limits, it retained its name west of Western Avenue, where Wellington ends.4 Since there were no major physical changes to Wellington Street specifically in this period, today's post will look at traffic in general on Ottawa's Wellington Street.

Jacques Gréber's Downtown plan, 1939

When French planner Jacques Gréber had first entered the picture in the late 1930s to consult on the National War Memorial,5 he expressed concern at Prime Minister King's choice of location for the War Memorial at Confederation Square and its chaotic effect on traffic,6 instead preferring Major's Hill Park. His initial consultation on Confederation Square expanded into a downtown beautification plan in 1939,7 which recommended replacing the Daly building with a new gyratory (essentially, a roundabout) connecting Wellington to Mackenzie and Sussex, and making Wellington one-way westbound around the new war memorial on Confederation Square.8 This led to a one-way triangle around Confederation Square being piloted in 1939,9 which survived until at least the 1960s.10

Gréber also proposed a new landscaped boulevard on the north side of Wellington, west of Bank Street, including "double rows of trees on either side".11 Unlike the Confederation Square plan, this would reduce space available for traffic flow, so in 1938 the City protested "that narrowing of Wellington street is contrary to the modern tendency towards wider thoroughfares to take care of the growing vehicular traffic." (emphasis added)12

Gréber's 1949 Plan for Canada's Capital

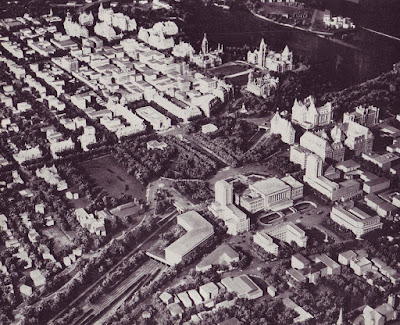

At the end of April 1949, Gréber's draft Plan for the National Capital was tabled in the House of Commons, with models in the Centre Block foyer.13,14,15 News coverage was extensive, including nearly a full page in the Ottawa Journal16 and an entire special section of the Ottawa Citizen.17 The final version would be approved and published the following year.18

The plan reemphasized the importance of Wellington Street as a "monumental artery to be strictly reserved as the approach to Parliament and Government Buildings". To that end, commercial traffic would be banned on Wellington east of Bay Street, streetcars would be replaced by buses,19 and a new bridge over the Rideau Canal (which we now know as the Mackenzie-King Bridge) would "serve as a by-pass relieving congestion on Wellington Street, Sparks Street, Queen Street and Confederation Place,"20 in conjunction with Albert and Slater which would be made one-way pair. The area around the Rideau Canal as Gréber planned it looks much different to what is there today:21

In 1947, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie-King had sought $100,000 in funding for the bridge, which "would drain traffic away from the Union Station-Chateau Laurier bottleneck; would provide an alternative route to that of Wellington street for trans-city traffic; would lessen traffic congestion in the vicinity of the Parliament Buildings; would be a bypass for traffic which might be held up by ceremonies at the National War Memorial …"22 and the bridge opened in 1951.23

"The western traffic approach to the new Mackenzie-King Bridge" actually extended through to LeBreton Flats and involved the construction of a link from Albert at Empress up to Slater and Bronson24 (traffic would also link from Wellington to Slater via the existing Commissioner Street connection).19 This would replace previous plans to connect Laurier to Albert with a tunnel under Nanny Goat Hill.19 Though its days are now numbered,25 the link currently has a field separating it from Albert Street, but it was built behind houses along Albert Street. Here's a photo of that Albert-Slater link under construction in 1951-1952:26

Only the building at the far right (formerly a furniture warehouse and now a CCOC property) and the two houses between the utility poles are still there.

This photo in the Journal in August 1952 shows the link as it appeared shortly before opening. There's still a lane waiting to be paved on the left (south) side.27 The ramp was 900 feet long and 30 feet wide—four feet wider than Slater east of Bronson.24

This roadway will be removed soon (2021), with the City having approved of purchasing adjacent NCC land for the upcoming realignment of Albert Street which will make the Slater link redundant.28,29

The main connection to the west end

However, west of the new Albert-Slater ramps, traffic was still funneled onto Wellington Street through LeBreton Flats and onto the Wellington Street viaduct over the C.P.R. tracks (current O-Train Trillium Line), as we can see in this aerial photo from the late 1940s.30

On this map of land uses in 1946 produced by Gréber,31 we can trace Wellington Street and see just how much of the western part of the city (all of Hintonburg and Mechanicsville, for a start) was funneled onto Wellington Street to cross the C.P.R. tracks on its way into Downtown.

The Gréber plan therefore recommended the replacement of the cross-town railroad with "a cross-town parkway (a landscaped highway)"—i.e. Highway 417, the Queensway—"Thus the present routing through Ottawa via Eastview and Rideau street to Wellington will be regarded as a main artery for intense local traffic and would not be overloaded by interurban traffic."32

This was still some years off, so in 1956 the province officially designated Richmond Road and Wellington Street, from Carling and Richmond to Wellington and Bank, as Highway 15 ALT, an alternate routing to the main Highway 15 which went downtown via Carling and Rideau Canal Drive (now Queen Elizabeth Drive). This designation was decommissioned in 1960.33

The public weighs in on Wellington

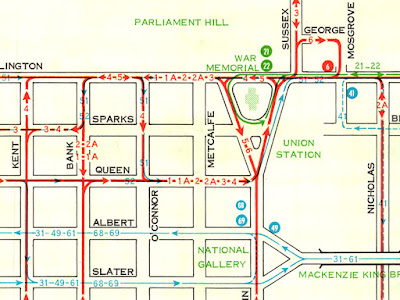

Aside from the Wellington Street Viaduct, which will be the subject of Part 8, traffic in Ottawa in general and on Wellington Street in particular was, as always, a hot topic in the pre-Queensway days of the 1950s. For context, here's the Ottawa Transportation Commission's public transit route map for 1951, showing streetcar routes in red, the trolley bus route in blue, and bus routes in green (including some going over the Wellington Street viaduct during rush hours):34

In 1946, the Ontario Minister of Highways, George P. Doucett, announced a two-million-dollar spending plan, including

One driver's letter to the editor published in the Ottawa Citizen36 describes the kind of complaint that typifies the frustrated driver that traffic engineers still cite today as the reason why pedestrians must push buttons to cross the street (he also complains about streetcars):

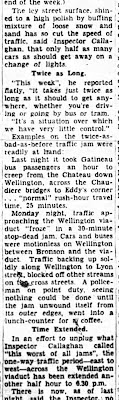

Traffic lights are a great thing, during rush hours and heavy traffic, but after midnight they are just a nuisance to through traffic.In a winter storm four days before Christmas, 1954, the "worst of all [traffic] jams" saw the Wellington Street viaduct freeze up for 30 minutes, stopping traffic (and blocking cross-street traffic) as far as Lyon Street. Gatineau-bound buses took an hour to get from the Château Laurier to the Chaudiére bridge. It was so bad, one police officer on traffic duty just gave up and went to get a coffee.37

At the corner of Musgrove and Rideau there is a long wait; with no traffic coming either way the same occurs at Sussex Street, then the Chateau, then at Elgin, then clear sailing till you get to Booth Street, another long delay, one at Wellington viaduct. In all there are 12 stop lights from the Union Station to Westboro, and the most useless of them all is the one at Clarendon and Wellington Streets, even in the day-time.

The following April, repairs on the eastbound lanes of the viaduct caused an even worse jam, where detoured morning traffic "took 35 minutes to get from Wellington around the Somerset detour and back to Wellington."38

An editorial in the Ottawa Journal on January 15, 1955,39 gets tantalizingly close to concluding that wider roads are not the answer, instead merely lamenting that roads will never keep up:

"Motor vehicles pour from the factories and the used-car parks on to the streets and highways like locusts swarming for the greener pastures and every year there are more of them than in the year before. But it is just not possible to increase the highway space to match the demands upon it, or to widen bridges over night or eliminate bottlenecks, or provide more abundant parking space.

So it is that we never have a chance to plan against the facilities traffic will require say in 1965 because we are trying in 1955 to remedy conditions building up since 1945. By the time we have turned Carling avenue into a six-lane highway the pressure on some other thoroughfares into Ottawa will be at the bursting point. And when a bridge is at the same time a bottleneck—the old Interprovincial for example, and the Wellington street viaduct over the railroad tracks—the remedy costs millions.

End of Part 6

Tune in next time for Part 7, where we'll continue looking at traffic in Ottawa and on Wellington in the second half of the 1950s, with a close look at a lengthy report on traffic and transportation in Ottawa by a U.S. traffic consultant.

One of the reasons for the long delay since posting Part 5 in January 2020 is that I had very little content after 1912 up to the 1950s. Hoping to fill in the timeline with some non-renaming details, I went back to the Ottawa Room and took out a subscription to Newspapers.com. This yielded considerably more information than I'd bargained for, and compiling it all into a useful narrative took most of February. Since I'd initially planned for this Wellington project to end by December 2019, I decided at the end of February put it aside and get on with life.

Only in late August (and over the 2020 December holidays, and in Spring 2021...) did I resume picking away at it and flesh out what was to originally be Part 4 and is now parts 5 through 8! Those will all be coming out in relatively quick succession, and I'm considering publishing this blog series as a book.

As always, I've done my best to filter out the wrong information and provide sources for the rest; corrections are welcome by email, tweet, or comment (all comments are moderated).

Show/hide references

- 1: ▲ City of Ottawa Act (1949), 1949, Referenced in Elliott (p. 256), I can't find a direct reference to the City of Ottawa Act (1949).

- 2: ▲ Elliott, Bruce S. The City Beyond: A History of Nepean, Birthplace of Canada's Capital 1792-1990. Corporation of the City of Nepean, 1991, p. 391 (Appendix 4).

- 3: ▲ Growth of the City of Ottawa 1855-1955 (Map), ca 1955, I've tried hard but I cannot find where I downloaded this from in January 2014. I also don't know what book it's from.

- 4: ▲ Note from blog author, I don't think it's possible to reference the absence of a decision to rename a street; I am asserting this myself. The renumbering of Richmond Road buildings would have been quite a headache if they had!

- 5: ▲ Gordon, David L. A. Town and crown: an illustrated history of Canada's capital. Invenire, 2015, p. 182.

- 6: ▲ Haig, Robert. "1937." Ottawa, City of the Big Ears, 1975, p. 195. King admitted years later he may have erred in locating the Memorial, according to this reference.

- 7: ▲ Gordon 2015 p. 185.

- 8: ▲ "French Architect Plans For Beautifying Center Of Capital Announced." Ottawa Citizen, 1938-02-08, p. 11. This was a feature on the cover of the second section.

- 9: ▲ "Trying Out New Traffic Regulations." Ottawa Journal, 1939-01-16, p. 12 Col 5.

- 10: ▲ "Folder containing scanned and PDF historical Ottawa transit maps." Maps, Data and Government Information Centre (MADGIC). Carleton University MacOrdrum Library, Accessed on 2020-01-15, OTC Ottawa Bus Routes, November 1962.

- 11: ▲ "The Capital Their Majesties Would See Twenty Years Hence: Jacques Greber Reveals Interesting Scheme for A More Beautiful City." Ottawa Citizen, 1939-05-16, p. 29.

- 12: ▲ "Board Opposes Tracks On Sparks Street." Ottawa Journal, 1938-03-18, p. 15 Col 1.

- 13: ▲ Gordon 2015 p. 197. Note that the DRAFT plan was tabled in the House on April 29, 1949, but the FINAL report was released, i.e. published, in 1950. Gordon notes on page 196 that 'A 300-page draft report was completed in 1948 and circulated to numerous agencies for comment.'

- 14: ▲ "Greater Ottawa Report Will Be Tabled Today." Ottawa Citizen, 1949-04-29, p. 1.

- 15: ▲ "Set Up Models Of Capital Plan In Centre Block." Ottawa Journal, 1949-04-29, p. 20.

- 16: ▲ "Vast Changes for Greater Ottawa Under Capital Plan." Ottawa Journal, 1949-04-30, p. 10.

- 17: ▲ "Vast Outlay For Greater Ottawa Program: Report Embraces 33 Road, Rail and Building Projects." Ottawa Citizen, 1949-04-30, p. 21. This is the cover headline for an entire section of the paper devoted to the Capital Plan.

- 18: ▲ Gordon 2015 p. 198.

- 19: ▲▲▲ "One-Way Streets To Handle Traffic From New Bridge." Ottawa Journal, 1949-04-04, p. 16 Col 3.

- 20: ▲ Gréber, Jacques. Plan for the National Capital. National Capital Planning Service, Ottawa, 1950, p. 171.

- 21: ▲ Gréber 1950 Plate 118.

- 22: ▲ Sykes, A. R. "Mr. King asks for $100,000 for Ottawa bridge." Ottawa Journal, 1957-07-07, pp. 3 Cols 5-6. Article starts on page 1, reference is on continuation on page 3.

- 23: ▲ Haig 1975 p. 210.

- 24: ▲▲ "FDC Buying Property For Bridge Link." Ottawa Citizen, 1951-03-07, p. 15 Col 1.

- 25: ▲ "Reconstruction of Albert Street/Queen Street/Slater Street from Empress Avenue to Bay Street and Bronson Avenue from Queen Street to Laurier Avenue." City of Ottawa website, Accessed on 2020-08-25, Detailed design is underway for a complete overhaul of the Albert/Slater/Bronson/Commissioner area, with utility relocations in 2021 and construction in 2022 and 2023.

- 26: ▲ OttawaHH (Ottawa's History and Heritage in Pictures), The photo was emailed to me by Robert Smythe but I suspect it also appears in a collection at OttawaHH (possibly supplied by Robert). If anyone knows I'd be happy to update this citation.

- 27: ▲ "$80,000 bite out of Nanny Goat Hill (Photo with caption)." Ottawa Journal, 1952-08-06, pp. 3 Cols 3-6.

- 28: ▲ "Finance and Economic Development Committee, Tuesday, April 6, 2021, Agenda and Action Summary." City of Ottawa website, Accessed on 2021-04-24, Item 5: AGREEMENT OF PURCHASE AND SALE WITH THE NATIONAL CAPITAL COMMISSION FOR PROPERTY REQUIREMENTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE ALBERT STREET, QUEEN STREET, SLATER STREET, BRONSON AVENUE RECONSTRUCTION PROJECT (ACS2021-PIE-CRO-0004).

- 29: ▲ Hunt, Kathryn. "Albert/Slater design reveal: Public consultation on what bus corridors will become." The Centretown BUZZ, 2019-12-15, p. 1.

- 30: ▲ Gréber 1950 p. 242. Apparently Gréber credits Spartan Air Services for this photograph.

- 31: ▲ The National Capital Planning Service (J. Gréber) Dec 1946. "Land Use Plan, City of Ottawa." Ottawa Historical Maps. Carleton University MacOdrum Library, Accessed on 2019-11-25.

- 32: ▲ "New East, West, and South Approaches To City: Imposing Program Of Traffic Changes: Eastern Entrance Over New Bridge Spanning The Rideau At Hurdman's." Ottawa Citizen, 1949-04-30, p. 22.

- 33: ▲ "The King's Highway 15A (Alt.) Ottawa." The King's Highway. Cameron Bevers, Accessed on 2019-12-22, Try as I might, I couldn't find any references to Highway 15A in any newspapers or maps, aside from the ones from this website.

- 34: ▲ "Folder containing scanned and PDF historical Ottawa transit maps." Maps, Data and Government Information Centre (MADGIC). Carleton University MacOrdrum Library, Accessed on 2020-01-15, OTC Route Guide for City of Ottawa, 1951.

- 35: ▲ "Spend $600,000 On Ottawa Valley Highways This Year." Ottawa Journal, 1946-06-07, p. 1 Col 8.

- 36: ▲ Jones, A.L. "When Traffic Lights Delay [letter to the editor]." Ottawa Journal, 1951-09-25, p. 32 Col 7.

- 37: ▲ "Ottawa In Tightest Traffic Jam: Snow and Cold, Heavy Shopping Double Capital Travel Time." Ottawa Journal, 1954-12-22, p. 31 Col 6.

- 38: ▲ "Morning Traffic Jam In West End." Ottawa Journal, 1955-04-22, p. 1 Col 1.

- 39: ▲ "We Never Catch Up With Traffic [Editorial]." Ottawa Journal, 1955-01-15, p. 6 Col 1.

No comments:

Post a Comment