Part 7: Dawn of "Modern" Transportation Planning in Ottawa

If A.E.K. Bunnell's 1946 report covered in Part 5 recommended a few tweaks to the road network, and the 1949 Gréber report we looked at in Part 6 reimagined large swathes of the City's buildings and transportation network, a January 1955 report report on traffic and transportaion in Ottawa by consultants Wilbur Smith & Associates came in somewhere in the middle. No renamings or disconnections of Wellington Street in this installment, this time we're going on full traffic nerd mode.This 245-page report1 took a detailed snapshot of traffic in Ottawa, and made a number of specific recommendations, many of which involved Wellington Street. In today's part of the Wellington Street blog series, we'll dive into this report and see what it had to say about traffic in general, and Wellington in particular, in the mid-1950s.

1955 Traffic and Transportation Plan for Ottawa

The detailed report from consultants Wilbur Smith and Associates of New Haven, Connecticut, entitled "Traffic and Transportation Plan for Ottawa, Canada," had a blunt conclusion about the state of transportation planning in Ottawa:2

"Present traffic responsibilities and controls are almost entirely in the hands of City Council. No substantial powers have been delegated with regard to traffic regulations and traffic control matters. Even the trivial traffic control functions are considered and acted upon by the Council."The report gleans lots of information about the status of Wellington Street in the mid-1950s. The report reinforced what we already knew, that "Wellington Street and its extension, Richmond Road, form the principal trafficway serving western portions of Ottawa."3

They make this visually apparent on the isochrone chart in Figure 14, which uses Confederation Square (i.e. the east end of Wellington Street) as the middle of town from which is measured how far you'd expect to get in

The report text also indicates that travel time on Wellington and Scott was faster than Carling to get to the west end, and the Isochrone chart certainly reflects this.5 You can see from the map that you can get to Richmond and Carling (i.e. via Wellington and Richmond) in a little over 15 minutes.

Just for kicks, I thought I'd see how that compares to today. Starting at 4pm on a Monday afternoon in August 2020 (i.e. lighter traffic due to both summer holidays and COVID-19), a similar route along Wellington, Albert, and Richmond would take between 20 and 45 minutes.6 (Google's suggested routes via the 417 or Sir John A Macdonald Parkway at the same timeframe are estimated to take bewteen 12 and 30 minutes.7)

Elsewhere, the report notes that "[a]s the streets approach the central district... Again it was found that Wellington-Rideau Streets were the principal travel arteries" and that "the entire street system of Ottawa tends to concentrate traffic through this single complex area [Confederation Square]", despite the presence of the relatively underutilized Mackenzie-King Bridge and the new feeder lanes into Albert Slater.8

This is illustrated on Figure 5, which shows movements across a screen line around the downtown core. Although Albert and Slater carry a fair amount of traffic, Wellington definitely carries much more into and out of downtown.9

The above figure only shows vehicles (so a busful of passengers counts as 1), but the report does indicate that of the 150,000 people entering the central business district daily in 1955, 39% arrive by car, 33% by transit, 18% as pedestrians, and 10% by truck.10 Compare that to Ottawa's modal share in 2016, where less than 30 percent of Ottawans commute by public transit and active transport combined!11

The report made a number of recommendations to try to relieve traffic from Wellington, such as converting Sparks and Queen to a one-way pair,12 "peak hour curb restrictions" (i.e. no stopping) on the south side in the morning and on the north side of Wellington Street in the afternoon, all the way from Bank Street through to Golden on Richmond Road.13

Wellington intersection recommendations

The 1955 report dedicated a number of pages to traffic signals—providing us with a snapshot of how many signals were in Ottawa at the time—and recommended that many more intersections be signalized. This figure (click for full page) shows the traffic signals in downtown Ottawa.14

In addition to recommending the replacement of the traffic islands installed at four intersections of Wellington Street in 1929 (see Part 5) with "standard signals",15 the report recommends coordinating the timing of traffic signals on Wellington to permit "progressive speeds of about twenty-three miles per hour [37 km/h]",3 and these speeds are "commensurate with road user desires."16

This principle, known today as a "green wave," is illustrated for Wellington Street in Figure 22, below:17 time is on the X axis, and the five cross streets, Lyon, Kent, Bank, O'Conor, and Metcalf[e] in the Y axis. Each cross street's signal timing is shown with the east-west green light in bold. Dark "through bands" show the paths of motorists going in each direction and where they intersect each green light. The report notes, "By providing an exclusive left turn lane, in addition to two through moving lanes in each direction along street, capacities are substantially increased. The "band capacities" of about 1,000 vehicles per hour in each direction should accommodate most traffic demands."3

This is a style of visualization that has eluded me for many years, and now that I've seen it, I want to see one for every street in Centretown! I can never quite go fast or slow enough on my bike to consistently hit green lights on Laurier or Somerset. Often if the signals are optimized for one direction, they're awful in the other direction (or awful in both, if the timing is optimized for the cross streets).

The report's tenth chapter looked at 12 problematic intersections, Confederation Square, and the stretch of Elgin between Albert and Lisgar. It recommended "remedial measures possible without extensive physical constructions".18 Five of these 14 locations are on Wellington Street (including Confederation Square and the Richmond/FDC Driveway intersection—now Wellington Street West and Island Park Drive). "Offset, multiple approach and plaza type intersections are frequently found in the City; these have become focal points of accidents, confusion, and congestion."19

The report's descriptions and diagrams of how they'd fix these intersections gives us some insight into how they looked and operated at the time.

Wellington-Sparks-Fleet-Commissioner

Moving further west from the Central Area traffic signal map above, the "South Central Signal System" map20 shows actual and recommended traffic signals in LeBreton Flats. A callout on the map roughly outlines the stretched X shape junction at Wellington, Sparks, Queen St West, and Commissioner, which the Board of Trade described in a September 1947 report as "a traffic trap".21

The asphalt for much of this intersection is still present, connecting what is now Cliff Street and Pooley's bridge with Commissioner street at the LRT tunnel west entrance.

I'm particularly interested by the markings which show the signal timings for these intersections; a detail which often isn't important enough to make it into official records (nor that the signal for traffic coming from Commissioner only operates on request). Actually, the graphic doesn't show that either; rather it's the recommended traffic signal setup for this intersection.

The detailed drawing for this intersection gives us a sense of the general geometry of this intersection, including some dashed lines for the current extents, which is not something you can really appreciate from blurry aerial photos. Not shown is the traffic circle at Wellington and Fleet that would be removed. It is referenced in a 1954 Ottawa Journal article about traffic to the Chaudière crossing.22 Considering the complicated three-phase signalization and seven overall lanes to handle all the different movements, it's not hard to imagine why the prior generation of traffic people just threw in a traffic circle instead of figuring out a solution for this bottleneck:23

The text accompanying the above diagram gives us more clues about the intersection's appearance:18

"Wellington Street at Fleet and Sparks Street: The street railway tracks along Wellington and Fleet Streets are currently being removed. It is desirable to integrate channelizations and signalizations with the planned resurfacing. Accordingly, Figure 42 was prepared to show recommended revisions.According to a traffic report in the Ottawa Citizen, this intersection was signalized in (or just before) January 1958, which led to many cars being unable to get moving on the uphill slope when the light turned green in a snowstorm!24

Three moving lanes along Wellington Street in each direction are separated by a median in which a fourth lane for left turns is provided at key locations such as at Fleet Street. The traffic signals at the Fleet-Wellington-Commissioner intersection are interconnected in the south-central sixty second signal network. The signal timing gives vehicles positive periods in which to negotiate movements.

Wellington-Broad-Albert-Rochester

A little further west is the intersection of Wellington, Broad, Albert and Rochester, another stretched intersection. It's barely recognizable today, since the only surviving part of the road network is the single road going east-west as I'll cover in later installments. In addition to carrying the brunt of vehicular traffic downtown on Wellington, this intersection also had to accommodate streetcar traffic on Albert, and cross traffic from the offset Broad and Rochester streets.25

Like the previous intersection, this intersection was suggested to be integrated into the south-central signal system. "By providing the principal east and westbound movements in separate phases, excellent east-west progression can be attained on both Wellington and Albert Streets." The east-west traffic was further optimized in this recommended design by making Rochester Street one way northbound and forcing southbound traffic on Broad Street to turn right onto Wellington westbound, and these two directions share a third signal phase which would only be activated on demand.26 This was illustrated in Figure 36:27

The City's 1959 budget included around $3,500 for this "congested" intersection to be "remodelled" with standard signal lights instead of the existing flashers.15

First Advanced Green signals in town

Continuing down Wellington over the Viaduct, we get to the West Side signal system, starting with a trio of coordinated signals at the intersections of Wellington, Somerset, and Bayswater. For these and the other West Side signals along Wellington (shown below28), the report recommends a "50 second cycle [which] develops progressive speeds ranging from 23 to 25 miles per hour. Multiple offsets should be provided at several locations to favor prevailing peak directional flows."3 It recommends that the signals only change when activated "because of the relative unimportance of most cross streets."29

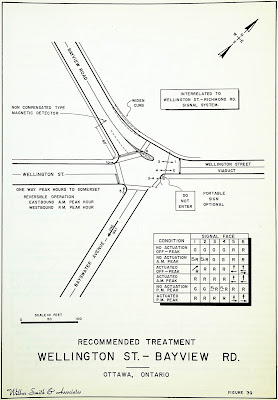

The report proposes mainly signaling changes at the intersection where Wellington, Bayview, and Bayswater meet to connect with the viaduct, in order to facilitate the reversible one-way route over the viaduct during peak traffic hours.30 As seen on the drawing below, the only physical change is a small slice of land that is proposed to be used to widen the curve up from the viaduct to Bayview.31

As with the other intersections, changes to the Wellington/Bayview/Bayswater/Viaduct intersection were made at the end of the decade. A March 18, 1959, article in the Ottawa Citizen announced that this would be one of two intersections in Ottawa to use the new "Advanced Green" signal: "The green signal will flash for a specific period, permitting traffic to make uninterrupted left turns while vehicles moving in the opposite direction face a red signal. The flashing green likely will be on for 15 seconds during rush periods and seven to eight seconds in off-peak hours."32

Flashing green signals for protected left turns were discontinued province-wide at the start of 2010.33

1949-1953 Collision Statistics

Being a traffic report, we also get traffic collision statistics (they use the outdated term "accidents"), which nowadays are released annually. One data table shows the 25 highest collision locations in the five-year period of 1949-1953, three of which are on Wellington Street:34

I copied those numbers from Table XI into a Google Sheet for analysis. As you can see below, the unsignalized intersection at Wellington/Lyon is eighth in terms of total collisions, but first for collisions with personal injuries over the five-year period. Wellington at Parkdale and Wellington and Holland, at #13 and #15, respectively, are the only other intersections on Wellington to crack the top 25 (perhaps all that traffic keeps people from going fast enough to crash?).

Table IX also gives a breakdown of all 1,906 collisions reported in 1953 divided into 10 types of collision. By 1953, the report surmises, "the accident toll has now leveled off at about 1,900 accidents and 20 deaths per year. This death rate of about 10 fatalities per 100,000 persons is high for cities of comparable size."35

Part VII of the report makes a number of recommendations to Ottawa City Council about how they should administer traffic matters. Opening with the quote at the start of this post, the report recommends that City Council stick to policy decisions about traffic, and thus "relieve the members of the City Council of the burdensome details of making decisions on traffic devices and regulations which could be handled effectively by traffic staffs".2 The report goes on to recommend the City create an entire traffic department to handle "the many problems of automobile transportation and parking ... on a full-time basis by a qualified traffic engineer with adequate staff,"36 and goes on to detail the budget and responsibilities of that department.

What came of it?

While a 1958 report by Urwick, Currie is cited as the basis on which the City's Board of Control and Ottawa Transportation Commission (precursor to OC Tranpso) decided to remove streetcars in favour of buses,37,38 the 1955 Smith report outlined a six-phase plan for phasing out streetcars in Ottawa, the staging of which was organized to "[enhance] the national capital by removal of tracks and wires from Wellington Street."

In fact, the Smith report notes that track removal from Wellington and Fleet was already underway. The first (removal of the Hull-St. Patrick line), second (Preston-George loop route) and fourth (Britannia line) phases would permit full removal of rails from Wellington Street, and the final phase would see the final removal of overhead streetcar wires used by the Bronson Ave. trolley bus route.39 Additional benefits of streetcar track removal include the ability to convert Albert and Slater to a one-way pair, further relieving Wellinton Street traffic and the 'liquidation' of the Champagne streetcar barn and relocation of the "centre town bus garage" to a more suitable location.

Also on Wellington

Various other changes came to traffic in Ottawa in subsequent years. Metered parking was introduced in November 1959, including on Wellington Street.40 Policewomen were hired in February 1960 to issue parking tickets and to direct traffic during peak periods.41 The budget to add "An asphalt sidewalk with curb on the north side of Wellington street from Booth Street to Broad Street" was cancelled in 1960 in favour of projects elsewhere.42 In 1967, the huge citywide spending plan included $21,900 to reconstruct the sidewalks on the south side of Wellington Street between Rosemount and Somerset.43

De Leuw, Cather's 1965 Ottawa-Hull Area Transportation report (the one which proposed the Downtown Distributor) gave a description of traffic patterns in 1963, and noted that Wellington still played a key role. We can also see on the adjacent map that Wellington has among the highest traffic volumes in downtown Ottawa, however Carling has still higher levels, suggesting it has gained importance since the isochrone chart from the 1955 Smith report:44

This was before the Queensway had made its way downtown. A Scenic Drive tourist map of Ottawa from 1962 has this inset map which shows the progress of the Queensway. Carling Ave, Bronson Ave, Laurier Ave, Nicholas St, and Hurdman St carried traffic through downtown between the east and west legs of Highway 17:45

So, for the time being, Richmond Rd, Wellington St, Rideau St and Montreal Rd remained the only continuous route through Ottawa, but not for long...

Tune in next time for Part 8, when we take a deep dive into the Wellington Street Viaduct. In the meantime, check out the list of posts in this series.

As always, I've done my best to filter out the wrong information and provide sources for the rest; corrections are welcome by email, tweet, or comment (all comments are moderated).

Show/hide references

- 1: ▲ Smith, Wilbur & Associates. Traffic and Transportation Plan for Ottawa, Canada. Wilbur Smith and Associates (New Haven, CT), 1955.

- 2: ▲▲ Smith 1955 p. 185.

- 3: ▲▲▲▲ Smith 1955 p. 60.

- 4: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 38.

- 5: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 37.

- 6: ▲ "Wellington St, Ottawa, ON to Richmond Rd & Ottawa Regional Rd 38 (via Wellington and Richmond)." Google Maps. Google, Accessed on 2020-08-29.

- 7: ▲ "Wellington St, Ottawa, ON to Richmond Rd & Ottawa Regional Rd 38." Google Maps. Google, Accessed on 2020-08-29.

- 8: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 17.

- 9: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 21.

- 10: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 30.

- 11: ▲ Moor, Hans. "Ottawa Commute Census Data Show Growth in Cycling Commute (2017-12-12)." Hans On The Bike, Accessed on 2020-08-29, See the chart 2016 Canada Active Transportation and Public Transit commute modal share. Note that it's not an apples-to-apples comparison as this is citywide data whereas the 1955 statistics are only for trips into the downtown core.

- 12: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 48.

- 13: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 53.

- 14: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 58.

- 15: ▲▲ "Better Traffic Control." Ottawa Citizen, 1959-03-26, p. 25 Col 2.

- 16: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 57.

- 17: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 59.

- 18: ▲▲ Smith 1955 p. 86.

- 19: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 71. The other intersections are: Prescott Highway (POW Drive)-FDC Driveway-Preston Street; Henderson Ave-Mann Ave-Hurdman Road; Carling Ave-FDC Driveway-Fisher Ave; Gladstone Ave-Booth St (including SB Booth St); Greenfield Ave Diversion-Echo Drive-Mann Ave-Nicholas St (under the railroad bridge); Pretoria Ave-FDC Driveway-Isabella St-Elgin St; Avenue Rd-Echo Dr-Riverdale Ave; Bank St at Riverside Dr and at Riverdale Ave. The report's appendix also includes drawings for Bronson/Carling, the Byward Market, and Rideau/Sussex/Besserer, previously submitted in interim reports.

- 20: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 64. Click the image to see the full diagram, which extends down to the Glebe.

- 21: ▲ "New City Hall, Police Station Urged by Board of Trade." Ottawa Journal, 1947-09-10, p. 6 Col 1.

- 22: ▲ "Transpontine Traffic Drives Drivers Mad." Ottawa Journal, 1954-07-03, p. 3.

- 23: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 88.

- 24: ▲ "New Lights Cause Snarl." Ottawa Citizen, 1958-01-27, pp. 1 Cols 5-6.

- 25: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 47. The report also recommended that Rochester be paired (northbound) with Booth (southbound) to form 'an extension to the Chaudiere Bridge relief' and 'an ideal connector between the bridge and Carling Avenue.'

- 26: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 81.

- 27: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 81.

- 28: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 63.

- 29: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 65.

- 30: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 82.

- 31: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 85.

- 32: ▲ "Wellington Traffic Light Experiment." Ottawa Journal, 1959-03-18, p. 8 Col 7.

- 33: ▲ "Traffic-light signalling and operation." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Accessed on 2020-12-28, Reference 3, citing OTM Book 12, page 55: https://www.library.mto.gov.on.ca/SydneyPLUS/Sydney/Portal/default.aspx?component=AAAAIY&record=59cabe78-8aaf-4347-95ab-d6c066099015.

- 34: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 29.

- 35: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 27.

- 36: ▲ Smith 1955 p. 192.

- 37: ▲ Bond, Courtney C. J. Where Rivers Meet: An Illustrated History of Ottawa. Windsor Publications, 1984, pp. 110-112.

- 38: ▲ McKeown, Bill. Ottawa’s Streetcars: An Illustrated History of Electric Railway Transit in Canada’s Capital City. Railfare DC Books, 2006, pp. 180-181. Citing Ottawa City Council minutes 1958-08-05.

- 39: ▲ Smith 1955 pp. 157-160.

- 40: ▲ "By-law No. 346-59: A by-law of The Corporation of the City of Ottawa amending By-law Number 260-51." City of Ottawa Bylaws, 1959, 1959-11-02, pp. 995-1002. Metered parking was added to both sides of the street between Elgin and Lyon, and south side only from Lyon to Sparks.

- 41: ▲ Haig, Robert. "1960." Ottawa, City of the Big Ears, 1975, p. 219.

- 42: ▲ City of Ottawa Bylaws, 1960, 1961.

- 43: ▲ Appleton, Roger. "City program clears way for '67." Ottawa Citizen, 1966-03-01, p. 13.

- 44: ▲ De Leuw, Cather. Ottawa-Hull Area Transportation Study, 1965, p. 34.

- 45: ▲ "G3464_O8_1962_O88." Ottawa Historical Maps. Carleton University MacOdrum Library, Accessed on 2019-11-24.

No comments:

Post a Comment